Interview by Dominique Mirambeau

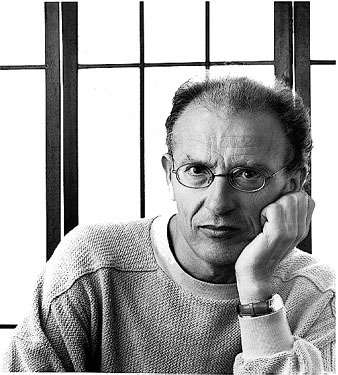

Moebius

– Jean, how MOEBIUS was born?

– How did I come across MOEBIUS? I came across MOEBIUS when I had to write a story for Hara-Kiri, which at the time was a bizarre satirical magazine. I thought it would be amusing to commit an act of rebellion by adopting a pseudonym.

– How do you see your creative world?

– My creative world is driven by pleasure above all else. Pleasure is the key to survival. There’s also an added bonus: being loved and admired by other cartoonists. That’s something that has always affected me—and still does. How do they see me? What do they think of me? Sometimes, it’s very gratifying to have these thoughts, and at other times, it’s quite terrifying.

– I’ve often had the feeling that cartoonists see me as a joker whose mask has fallen off. Almost like a ghost: MOEBIUS revealing himself for what he really is—mediocre. But it always surprises me to see how much they actually like me. It’s great! Hopefully, it lasts!

– How do you get in touch with that universe?

– Oh, it’s very easy! You just sit down at a table with a pencil and paper and let pleasure get to work.

It can also be difficult because things sometimes come to you as if they were covered in mist, in haze. They’re shrouded by resistance to creation, the absence of memory.

When you’re drawing, making a cartoon, it’s really the memory that’s at work.

– As a result of material released from memory, a kind of sensitivity to imagery emerges. This creates a current that runs through the hand, the eye, the paper, and suddenly provokes an emotion—the same emotion we feel when we see a drawing.

In fact, the drawing is born from traces left by emotion. Of course, there are all kinds of emotions: harsh, pleasant, light, and balanced.

Sometimes, beautiful drawings come from mysterious and unsettling sources. This happens to me when I’m drawing—I often wonder if I’m losing my mind.

You really feel like you’re losing touch with reality when you start drawing things that don’t have a recognizable reference. It feels as though you’re disconnected from yourself, doing something you don’t understand, as if you’re suddenly speaking a foreign language.

It’s both terrifying and exhilarating. Over time, however, you begin to trust the process. You realize you won’t die in this unknown world. The fear diminishes; you feel as if you’re in danger, but you’re not. So, you must keep going. Confidence is key: I’m on my way! And yet, the fear never completely fades—it remains just as intense.

-Tell us about your experience with films…

– It’s been very interesting, as it has brought me into close contact with a world I deeply admire—a world I’ve practically idolized since childhood. For me, cinema is something I keep returning to. It’s sacred. A movie is almost like a demonstration of divinity.

Directors are “gods,” in a sense—though, of course, in quotation marks. I hold cinema in very high regard, and I know I’m not alone in this. Many people feel the same way.

-How are you able to jump from one world to another?

– By creating cartoons and writing scripts, you gradually learn how to tell stories. And storytelling is the linchpin that connects different kinds of storytellers—in film, literature, comics, theater… The essence of storytelling is not merely literary.Doing cartoons on the one hand and scripts on the other, you learn bit by bit how to tell stories. And telling stories is the linchpin which connect the different kinds of story teller, in film, literature, strip cartoons, theater… The essence of which is not merely literary.

What does it mean to tell a story? It’s about entering sections of people’s lives, whether real or imaginary—it doesn’t really matter, as the imaginary is simply reality transposed and disguised.

It’s about expanding your own experience by stepping into the experiences of others. This is a uniquely human ability, one that helps us connect as part of a collective network.

Today, our consciousness is shaped by both our personal experiences and the collective “before” and “after”—assimilated from thousands of other beings. These experiences have been processed, reworked, refined, and synthesized into archetypal stories.

We integrate all of this into our consciousness. We become carriers of this collective consciousness, capable of holding ideas and concepts that, like aircraft, take off, return, get stored away, and then are relaunched, spreading their wings once more.

This resource is always at our disposal. It’s perfect! What a beautiful life…

– What has your experience been of using computers to create images?

As artists often say, the computer is nothing more than a sophisticated pencil. It’s simply a tool—nothing more, nothing less.

However, one cannot overlook its unique qualities, as every tool has its own distinct influence and can guide the artist into new creative realms.

-What do you think is the potential of virtual reality?

– If we continue on the path we’ve started, there’s a strong possibility that synthetic imagery will improve to a point where we can create realistic action.** We might even use imaginary actors who are indistinguishable from real ones. It’s both terrifying and marvelous. It will also be an incredibly advanced tool for creating and inventing stories. The moral dilemmas this will raise, of course, are countless. But we shouldn’t forget that this could become our grandchildren’s primary form of entertainment. We need to learn how to address these problems properly, whether legal or moral.

That’s the big question for humanity’s consciousness: what is real, and what is false?

With synthetic imagery and virtual worlds, we’ll be confronting a problem that will gradually become more prominent, appearing to drift away from its metaphysical roots, yet bringing us right back to them. It will be both marvelous and a great trap for humanity, especially if we push virtual reality to its logical conclusion.

What is the perfect virtual world? A dream. The day we can enter virtual imagery as though we are in a dream—that’s when humanity will confront its own destiny. Which is more worthwhile: living the dream of reality, or the dream of simulation? We’ll have to choose our dream.

The question will be this: will it be more worthwhile to live with the burden of the physical body, or to be put in suspended animation for twenty years, fed intravenously, and live in a dream world with imagined images—where some will act as directors, like gods? You see, we always come back to the idea of directing, of playing God!

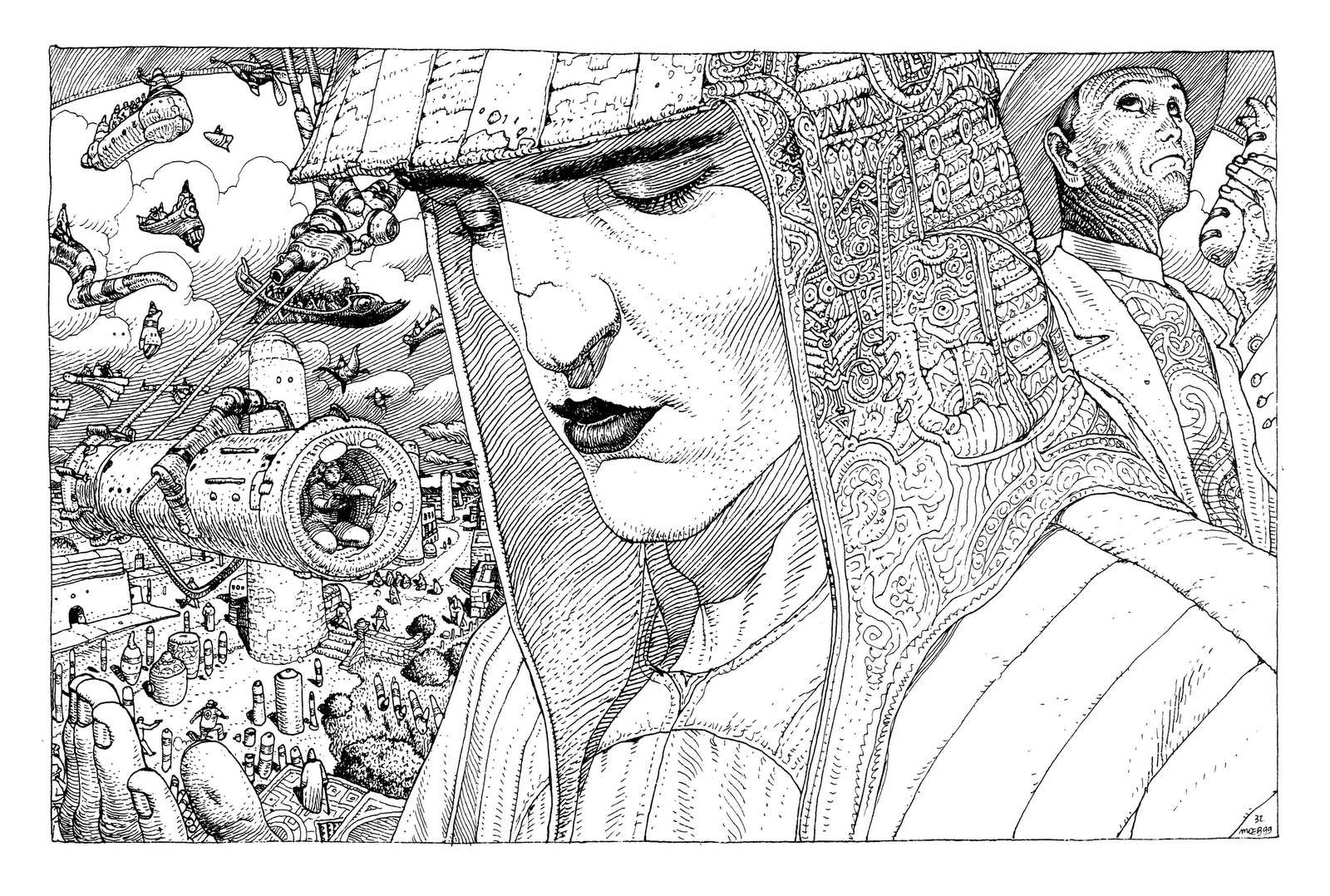

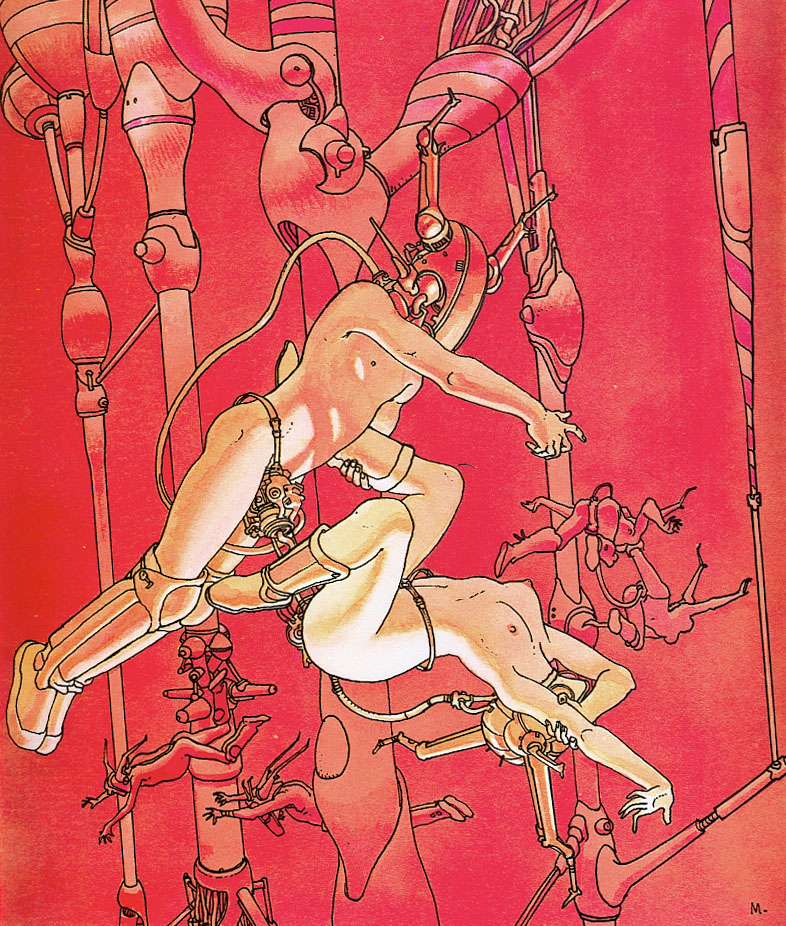

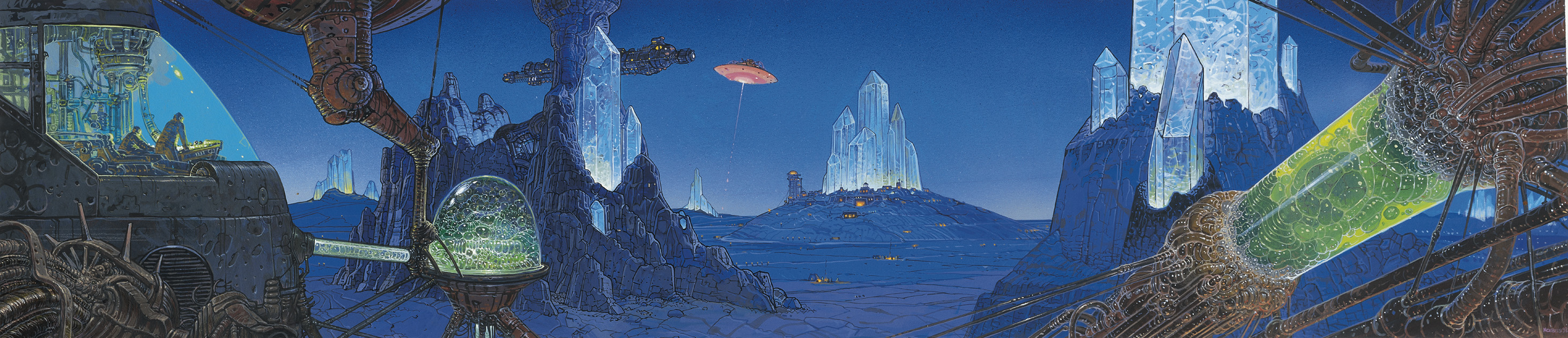

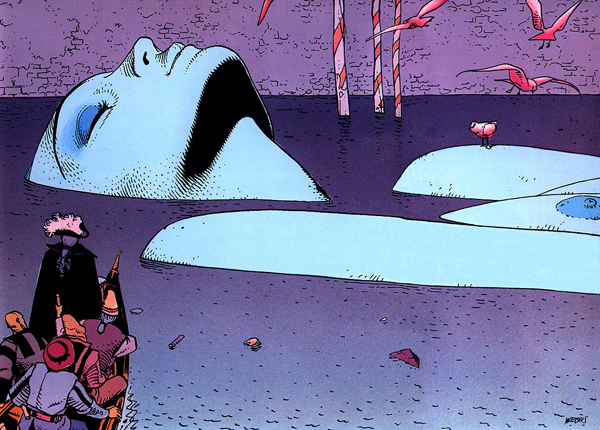

In 1975 Jean Giraud renamed himself MOEBIUS, inspired by the German astronomer who created the ring in the form of infinity. From this moment on, his work takes on a new dimension: Arzach, The Airtight Garage, The Long Tomorrow, The Gardens of Aedena, Les Yeux du Chat, Venice Celeste… are true masterpieces that stretch the limits of the classical comic and plunge us into unexplored universes.

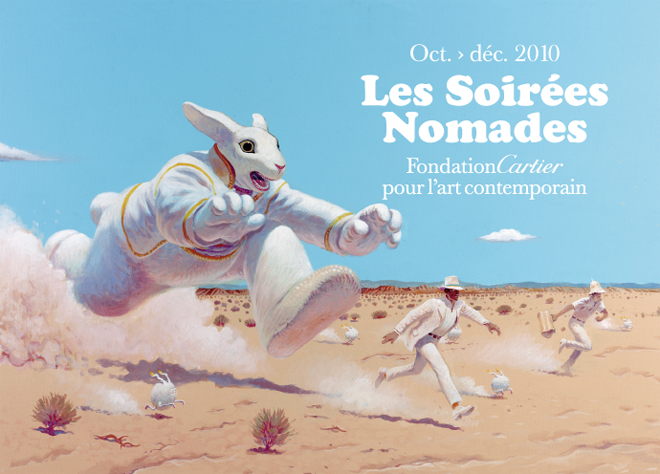

From the seventies onward, MOEBIUS began to take an interest in the world of cinema. First he took part – along with Alexander Jodorowski – in a frustrated attempt to bring Dune to the screen. Later he collaborated on Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), on Steve Lisberger’s Tron (1982), Rene Leloux’ “Le Maitre de Temps” (1982), Ron Howard’s Willow”(1988) and James Cameron’s Abyss (1989).

Text originally published in ArtFutura’s 1993 catalog.